Yves here. This post provides some useful analysis of US programs that encourage or mandate the Federal purchase of domestic goods. It also considers the employment impact. However, it skips over knock-on questions, such as whether increasing purchases of American goods is too unfocused to do much good in terms of competence and competitiveness, as in this policy is not terribly beneficial in the absence of industrial policy.

Needless to say, this piece highlights a problem for Trump’s DOGE program. Logically, a cost-fixated initiative should demand that US agencies buy the lowest cost products. But that conflicts with his imperative of trying to punish strategic competitors, most of all China, by lowering our trade surplus with them.

By Matilde Bombardini, Andres Gonzalez-Lira, Bingjing, and Li Chiara Motta. Originally published at VoxEU

‘Buy national’ provisions serve as non-tariff barriers to trade and are often defended as tools for job creation and industrial policy. This column examines the costs and benefits of current and anticipated future provisions under the Buy American Act of 1933, which discourages federal agencies from purchasing ‘foreign’ goods. Forged during the Great Depression, the Act continues to guide federal procurement in the US, and has been revised under both Democratic and Republican administrations. The findings indicate that while these policies may increase domestic employment, they come with rising welfare costs.

The ongoing policy debate over rising protectionism and stricter trade restrictions has sparked widespread dialogue among economists. Although recent studies have brought attention to the costs associated with tariffs (Fajgelbaum et al. 2020), evidence regarding the impact of non-tariff barriers remains limited (Conconi et al. 2016, Kinzius et al. 2019). One measure is the adoption of ‘buy national’ provisions in public procurement, which mandate that goods acquired by the federal government meet regional sourcing or manufacturing requirements.

These provisions, which serve as barriers to the import of goods, create welfare costs by reducing import shares compared to free trade conditions. When buy national clauses mandate that the government purchase higher-cost domestic goods, the resulting expenses are borne by taxpayers. However, proponents argue that sourcing goods domestically helps promote job creation and retention, prompting the question: what is the ultimate welfare cost of these policies?

In Bombardini et al. (2024), we address these questions by examining one of the longest-standing and most prominent examples of domestic content restrictions in public procurement: the US Buy American Act of 1933 (BAA). The BAA set a precedent by requiring federal agencies to prioritise “domestic end products” and “domestic construction materials” for contracts performed within the US that exceed the micro-purchase threshold, typically set at $3,500. The two key elements of the BAA are the requirements that, unless specific waiver conditions are met: (1) goods purchased by the US federal government must be manufactured in the US, and (2) at least 50% of the cost of components must be spent on US-produced inputs.

Forged during the Great Depression, the BAA has become a renewed source of debate for several reasons. First, the landscape of globalisation has changed significantly since its inception, characterised by substantial growth in trade volume and a shift in composition. Today, two-thirds of global trade comprises intermediate goods (Johnson and Noguera 2012, Antràs and Chor 2022), which influences the BAA’s impact. Additionally, the BAA laid the groundwork for various domestic-content mandates, such as the Federal Highway Administration’s “Buy America” policy and the “Build America, Buy America” provision in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Finally, the BAA has been subject to reforms under both the Trump and Biden administrations: the most significant changes in nearly 70 years are set to make the BAA increasingly restrictive by 2029. This change guides one of our counterfactuals.

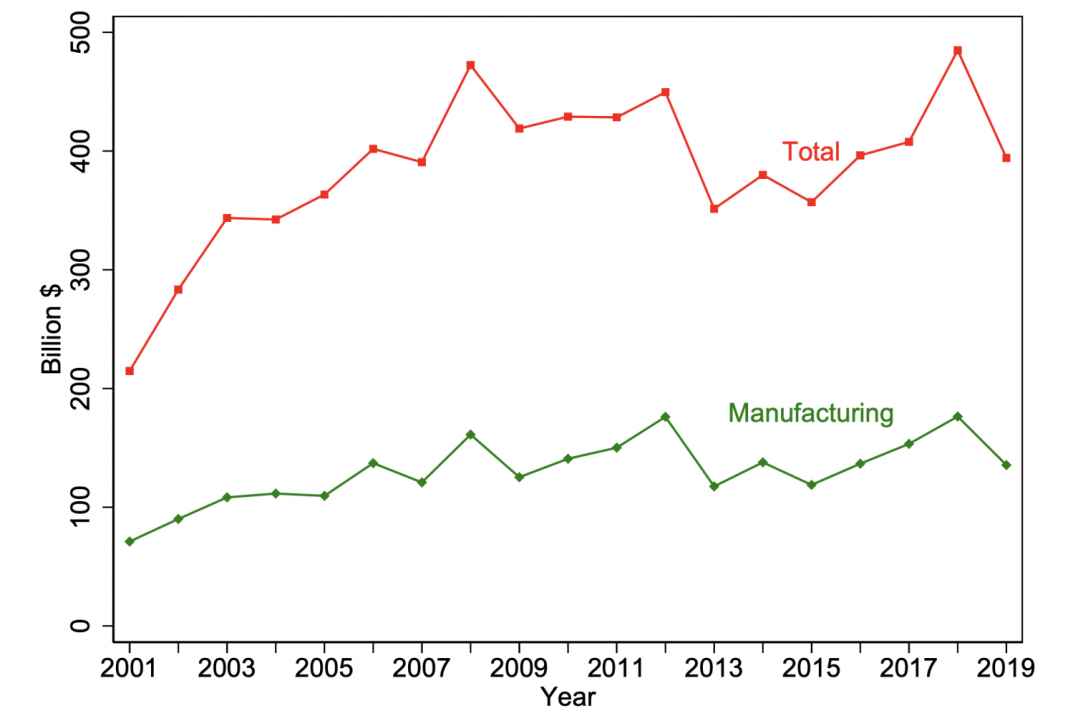

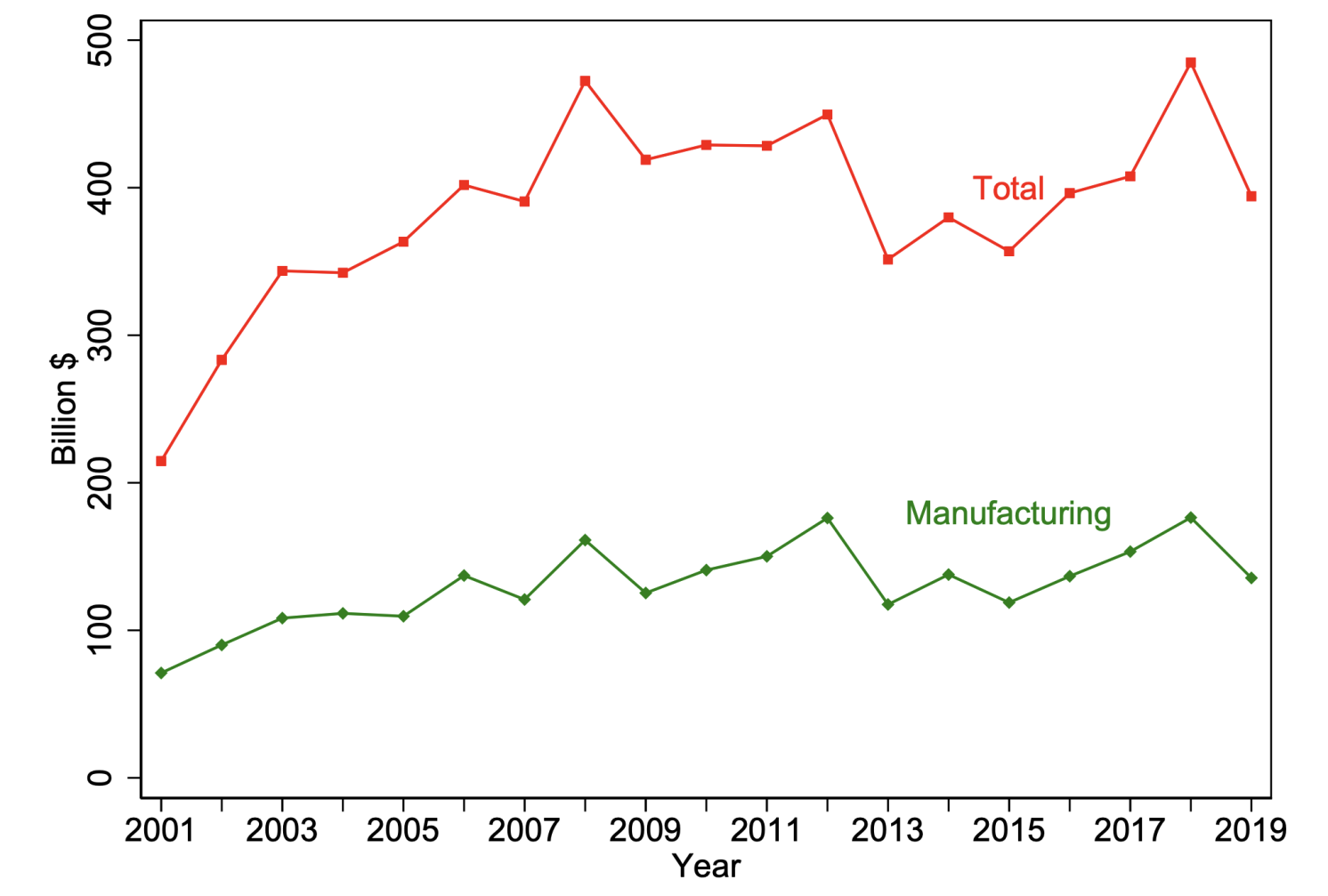

In our analysis, we leverage micro-data from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) covering all federal procurement contracts from 2001 to 2019. This comprehensive dataset provides insights into contract values, product/service sector codes, and the geographic locations of both purchasing agencies and producing firms (including their domestic or foreign status). Figure 1 shows trends in annual procurement spending, with the red line representing total spending across all categories and the green line focusing on manufacturing contracts. Between 2001 and 2008, procurement spending doubled and then stabilised at approximately $400 billion annually. Manufacturing industries make up about one-third of this spending and encompass various sectors.

Figure 1 Federal procurement spending, total and manufacturing only, 2021–2019

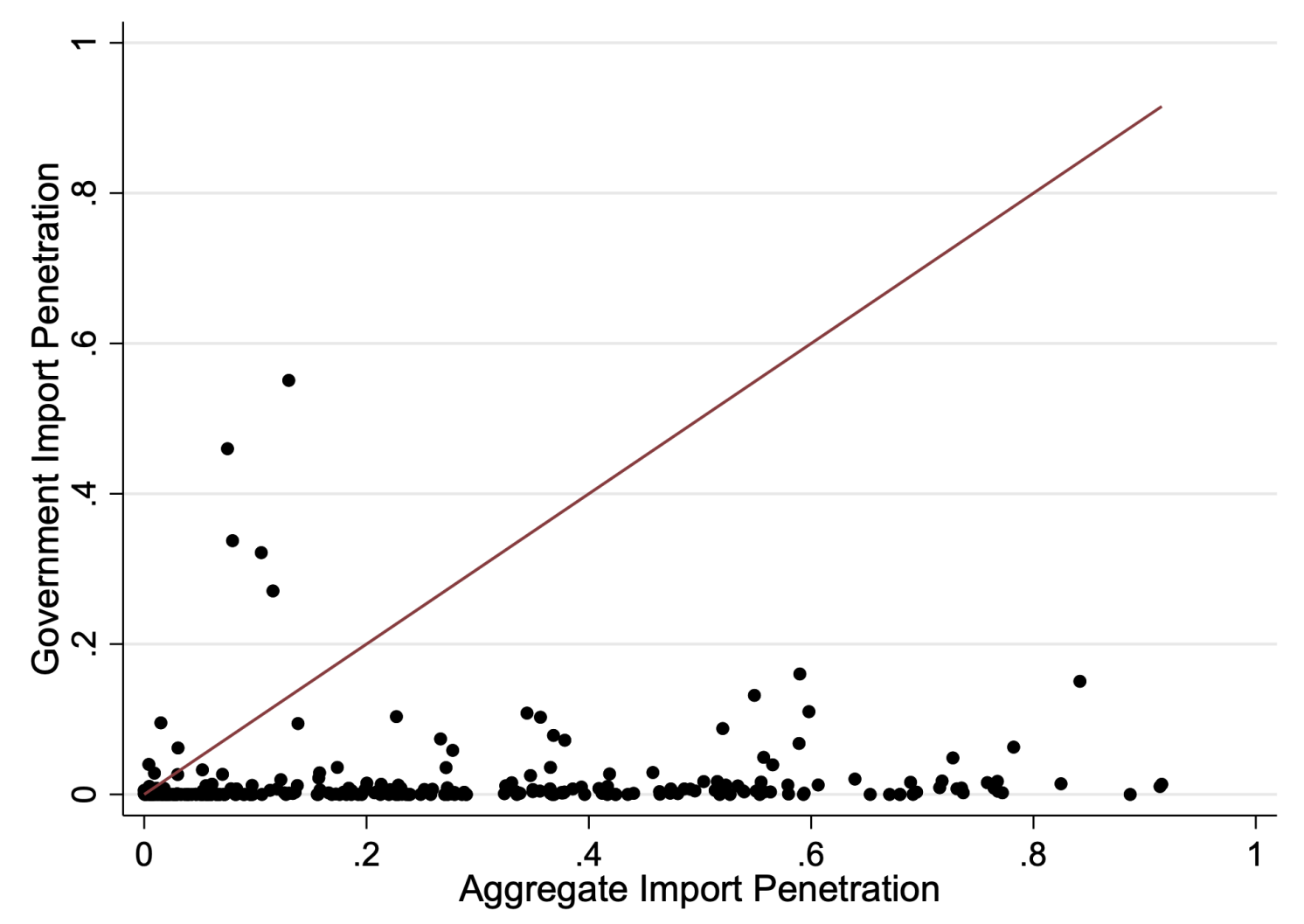

A major advantage of these granular data is their ability to reveal, industry by industry, the share of government consumption supplied by foreign firms, allowing for comparisons with the import penetration of private consumption. This comparison highlights how much more constrained the government is than the private sector in its ability to source goods. In Figure 2, we show how industry-specific (NAICS6) government import penetration ratios are significantly lower than aggregate figures. Most industries fall to the left of benchmark values from Hufbauer and Jung (2020) and Mulabdic and Rotunno (2022), calculated using international input-output tables which cannot distinguish import usage by final consumer (government versus households).

Figure 2 Aggregate and government import penetration ratios at NAICS6 level, only manufacturing

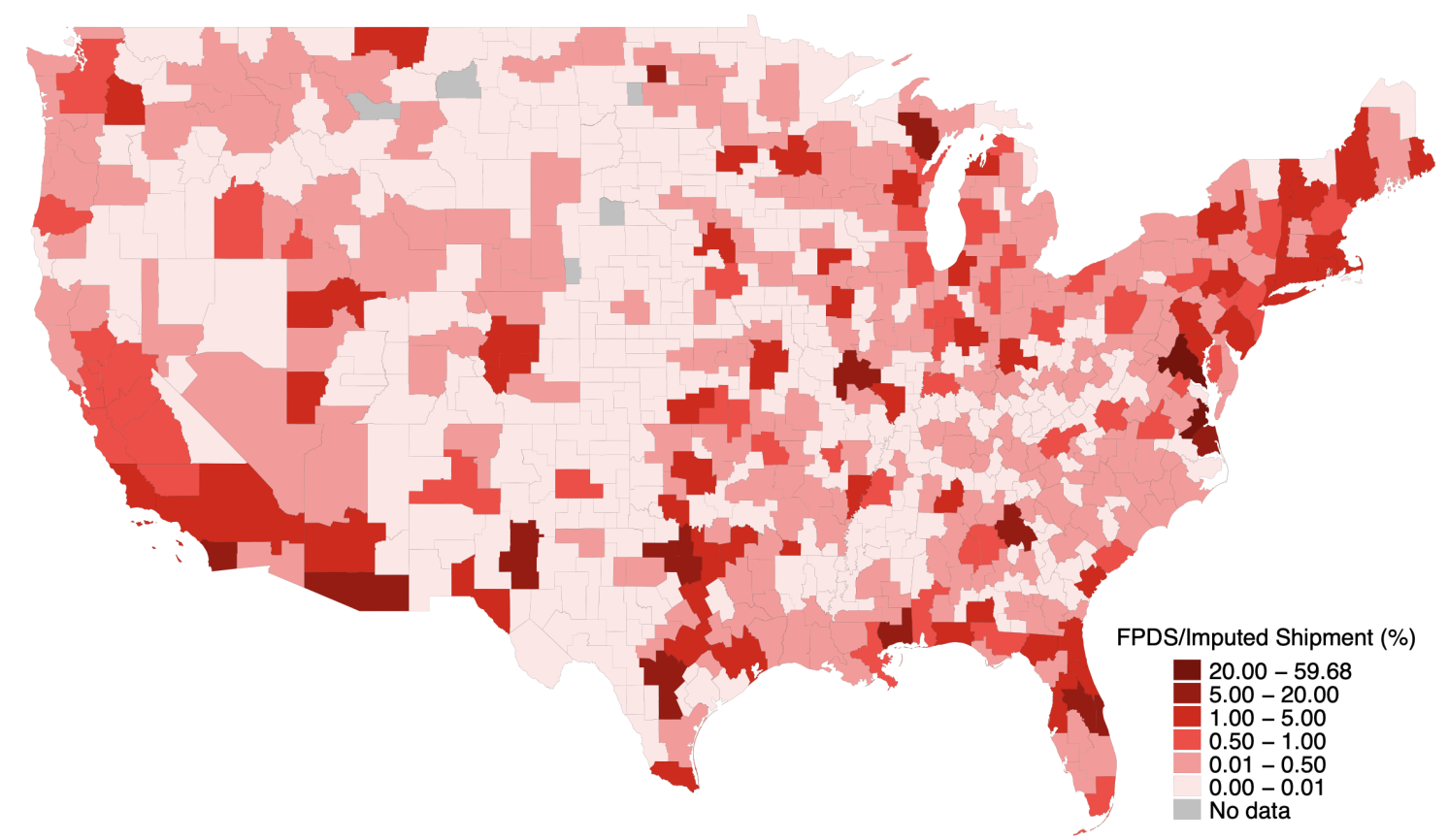

A second advantage of our data is that they allow us to map the geographic distribution of government purchases. Figure 3 reveals significant spatial variation in procurement shocks across US commuting zones. Using a shift-share instrument, we highlight the sizable impact of procurement spending on labour markets: an increase of $2,947 per worker (equivalent to one standard deviation) in government spending on goods produced within a commuting zone over a five-year period boosts manufacturing employment as a share of the working-age population by 0.47 percentage points.

Figure 3 Ratio between federal procurement spending and total shipment at the commuting zone level

To assess the welfare costs and benefits of the BAA (including employment and industrial policy considerations), we extend the quantitative model in Caliendo and Parro (2015) to include features relevant to the BAA. Consumers’ welfare depends on their consumption from both private market goods (as in traditional models) and public goods produced across different US regions (e.g. national defence and national parks), funded by the government through labour taxes. However, due to BAA provisions, firms producing for the government face higher trade barriers and production costs than those in the private market, affecting both final and intermediate goods. We include workers’ labour supply decisions across sectors and with respect to non-employment, and we account for sector-specific external economies of scale, where productivity is influenced by overall sector employment. Within this framework, stricter government policies on sectors with strong economies of scale could improve welfare.

By combining our model with a comprehensive trade matrix that includes both government and private consumption, as well as final and intermediate goods, we provide the first quantification of the effective trade barriers imposed by the BAA. Our findings indicate that BAA restrictions on final imports are significant, leading to a 96% reduction in government imports for the average manufacturing industry. Although the current wedges on intermediate inputs are not yet restrictive, upcoming changes are expected to extend their impact to several additional sectors.

Driven by these results, we use our model to conduct a series of counterfactual exercises by applying the exact hat algebra method (Dekle et al. 2007) and examining the potential effects of announced and possible future changes to the BAA. We first simulate the impact of lifting BAA-related import restrictions, effectively creating a scenario of free trade for the government sector. This change would result in an estimated loss of approximately 100,000 manufacturing jobs, at a cost of $132,100 to $137,700 per job in terms of equivalent variation. However, we recognise that completely removing these provisions is unrealistic for industries connected to national security. To address this dilemma, we use a specific clause in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to identify sectors with national security concerns. Incorporating this consideration only slightly reduces the magnitude of our estimates.

Second, restrictions on foreign intermediate inputs are set to become considerably tighter under policies introduced by both President Trump and President Biden, raising the minimum required share of US components from 50% to 75% by 2029. Our model predicts that this tightening will increase domestic employment by 41,300 manufacturing jobs. However, this comes at a substantial welfare cost, estimated between $154,000 and $237,800 per job. The “increasing cost of Buying American” thus arises from two primary factors: first, newly protected sectors that compete with foreign intermediate inputs generally have a lower labour share compared to those shielded by final goods restrictions. Second, regions most impacted by the increase in input costs are those with significant government procurement activity, resulting in higher public goods procurement costs.

Regarding external economies of scale, we uncover two significant findings. First, when running counterfactuals with and without external economies of scale, we observe that most of our prior results remain largely unchanged. This indicates that the current stringency of the BAA does not align with the strength of external economies of scale. In other words, BAA provisions are not targeted effectively at sectors where industrial policy could yield the greatest benefits. Inspired by this insight, we conducted an exercise whereby BAA wedges were redistributed across sectors to align perfectly with the strength of economies of scale. This adjustment resulted in a modest welfare gain of $3.69 per capita, accompanied by an employment reduction of 13,700 jobs.

Taken together, our findings suggest that while these policies can enhance domestic employment, they also come with increasing welfare costs, raising questions about the economic implications of strengthening domestic content requirements in government procurement.

See original post for references