One of the striking characteristics of the neoliberal era has been the dramatic decline in trade union membership across the world. The decline has also been associated with depressed wages growth for workers overall, increased income inequality, reduced job security, and the rising domination of the ‘gig’ job phenomena. Related trends include rising household indebtedness (as wage suppression has led to use of credit to maintain consumption levels) and reduced housing affordability, etc. Today (December 9, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest edition of biannual – Trade union membership – for August 2024 (the latest data available), which shows that trade union membership has grown from 12.5 per cent in August 2022 to 13.1 per cent now. But that modest rise doesn’t hide the fact that trade unions are no longer serving the role as a – Countervailing power – in the labour market. The decline has many drivers and many consequences and I consider that topic a bit in this post.

In his 1952 book – American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power – the great Canadian economist John Kenneth Galbraith argued that the classical liberal vision that bargaining between individuals over price and quantity would deliver optimal outcomes for all was naive in the extreme.

He noted the reality of large corporations with extensive market power to manipulate prices.

However, Galbraith noted that the irony of the trend towards a few large dominant firms had delivered what he considered to be highly productive and socially responsible outcomes, which ran against the view held by proponents of ‘laissez faire’.

So, what was the reason?

How could an economy that was defined by these powerful corporations, with both market and political influence, deliver acceptable outcomes for all?

In Galbraith’s assessment, it was the prevalence of what he termed ‘countervailing power’ that was the clue.

And he considered that the potential or actual abuse of power creates a dynamic where other institutions (private or state) form to counter the abuse.

On Page 116, he wrote that:

In this way the existence of market power creates an incentive to the organization of another position of power that neutralizes it.

In this regard, both State regulations and trade unions were considered to be essential bulwarks against market power abuse by corporations.

For example, on Page 118, he wrote that:

The operation of countervailing power is to be seen with the greatest clarity in the labor market where it is also most fully developed.

He argued that historically, “the individual worker has long been highly vulnerable to private economic power” whereas a consumer usually had a choice as to where to buy or whether to buy at all.

But in the development of American capitalism (Page 118):

Not often has the power of one man over another been used more callously than in the American labor market after the rise of the large corporation. As late as the early twenties, the steel industry worked a twelve-hour day and seventy-two-hour week with an incredible twenty-four-hour stint every fortnight when the shift changed.

No such power is exercised today and for the reason that its earlier exercise stimulated the counteraction that brought it to an end. In the ultimate sense it was the power of the steel industry, not the organizing abilities of John L. Lewis and Philip Murray, that brought the United Steel Workers into being. The economic power that the worker faced in the sale of his labor — the competition of many sellers dealing with few buyers — made it necessary that he organize for his own protection. There were rewards to the power of the steel companies in which, when he had successfully developed countervailing power, he could share.

So the rise of the trade unions became an important aspect in capitalist development to help ensure the abuses were reduced.

He also noted (Page 119) that:

As a general though not invariable rule one finds the strongest unions in the United States where markets are served by strong corporations …

The countervailing power role played by the trade unions also had a political dimension with the development of the social democratic political parties in the Post World War 2 period as the ‘political voices’ of the industrial unions.

Which, in turn, spawned a comprehensive industrial relations and social security framework that further repressed the abusive nature of big corporations.

Hence the role of the state was an important part of the countervailing force as the state acted as a sort of mediator between the conflictual ambitions of labour and capital.

Galbraith wrote that the dynamics of capitalism were such that the countervailing role played by unions would always be opposed and challenged by the corporations and that it was the role of the state, in part, to ensure, what he called “countervailance” factors remained operational and effective.

When I recently re-read the book, with the benefit of living through the neoliberal era to date, I realised that JK Galbraith had not fully appreciated the link between the corporate power and the political process, such that he largely ignores the capacity of the corporate elites and their networks to capture the legislative and regulative framework and reduce the countervailing threat to their ambitions.

And it is that capacity that helps explain the demise of the trade union movement since the peak years of the 1960 and early 1970s.

It doesn’t completely explain it – other factors such as the rise of the service sector with more difficult organising characteristics (more spread out, less large plants, etc), and the increased participation of women in the labour force, widening global supply chains – are also implicated.

And it is not as if the world has returned to some C19 laissez faire capitalism as the unions have declined.

Instead, the labour market power held by corporations has increased significantly and that is why wage suppression has been so effective in the last few decades.

It is also why, the inflationary episode in recent years was transitory and has petered out so quickly, compared to the 1970s when the initial supply shock (rising oil prices) triggered a distributional struggle between labour and capital that became a self-fulfilling inflationary force.

It has to be said that trade union statistics are notoriously unreliable with definitional issues, breaks in series, sampling variability, respondent error, variations in main job and secondary job, closures of large dominant companies in a survey year, and more making it difficult to piece together an historical narrative.

Having said that, we do have data that spans the ‘full employment’ era of the 1960s into the 1970s and the ‘neoliberal era’ that followed and persists today.

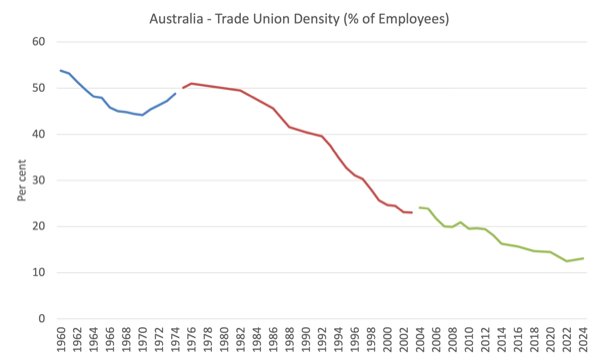

The following graph, incorporating the latest data from the ABS shows the trade union density as a percentage of all employees for Australia from 1960 to August 2024.

The different coloured segments (separated by the small gap between them) depict major statistical changes in definition or other reason.

But the message is fairly straightforward – there has been a dramatic decline in trade union presence in the Australian labour market since the mid-1970s.

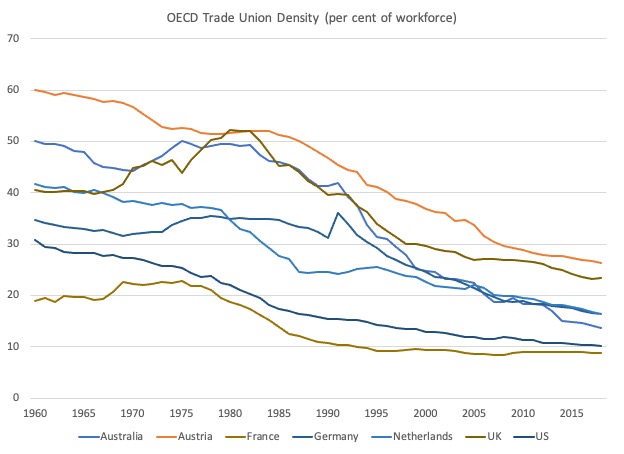

The trend depicted for Australia are not unique.

Here is a less updated graph for many of the advanced nations which shows the declines are widespread in the modern neoliberal era.

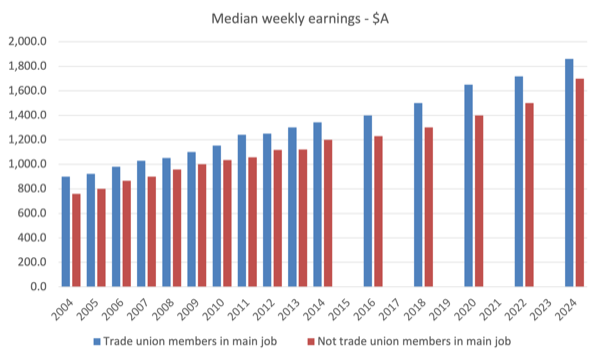

The link between the decline in Trade union membership and wage suppression is fairly clear.

The following graph shows the median weekly earnings for Australian workers split into trade union membership and non membership.

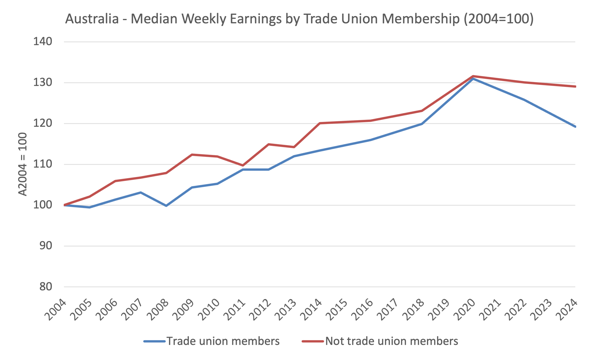

But it is also clear that union members in Australia have not been able to extract higher real Median Weekly Wages growth than non union workers (see second graph).

The growth of both segments in the workforce (unionised and non-unionised) have been very poor since 2004 (when this dataset started – don’t be fooled by the vertical axis).

And both segments of the workforce have endured significant real wage cuts in the last several years . Productivity growth has been much stronger over this period, which is why the wage share has collapsed below 50 per cent.

So even though union members enjoy higher median weekly earnings than non-union members, the unions have also had a hard time gaining wages growth for their members.

One of the reasons for the close link between outcomes is that while a growing number (and proportion) of workers in Australia do not join unions, they still choose to work under the relevant “union-negotiated enterprise agreement”, which means their fortunes rise and fall together with members.

This 2019 Research Discussion Paper from the RBA (RDP 2019-02) – Is Declining Union Membership Contributing to Low Wages Growth? – provides a lot of detail about all that, which is peripheral to my purpose today.

Trade unions formerly played a much wider role in society than just as a bargaining agent for wage negotiations.

The political role that they played cannot be understated and helps to explain, in part, why social democratic parties have become infested with neoliberal policy ambitions and no longer see themselves as presenting government as a mediating force in the labour-capital conflict.

The state in the neoliberal era now works more like an agent of capital now that the countervailing power of unions has waned.

One of the problems facing the union movement has been the increase in precarious, casualised employment, which is difficult to organise.

Further, government regulations have encouraged the growth of ‘independent contractors’, which is a major way that firms get around legal minimum wage and conditions requirements.

Everyone is an entrepreneur in this regard – and the capitalist who is really the only entrepreneur shifts the risk of the enterprise onto the workers, who are convinced that they are the entrepreneurs.

Think about the ‘gig’ economy in this regard.

At present, in Australia, the central bank (RBA) has gone rogue and is determined to push the unemployment rate up further (to around 4.5 per cent or another 100,000 odd workers losing their employment) because they are completely obsessed with the idea of the NAIRU.

Even though they cannot estimate the unobserved NAIRU with any precision they are persisting.

But back on the wages front, there is no threat coming from a wages explosion.

Quite simply, the workers have so little bargaining power now that extracting inflationary nominal wage rises is nigh on impossible.

Of course, the corporate bosses, who eschew any wage rise at all times, seize on any gains made by workers as being inflationary and they seem to have the ear of the RBA.

The bosses then claim they are justified in pushing up prices – using the wages smokescreen – and the RBA continues to push out the fear that an inflationary outbreak is looming and they cannot reduce interest rates.

So price gouging by corporations that now operate with little countervailing power in JK Galbraith’s sense is legitimised by the RBA as a ‘wages problem’.

And so the circle is complete.

Corporations operate with the imprimatur of the state to further entrench their power whereas, on the workers’ side, their political voice declines.

A further issue, which I will explore in another post sometime is the role that trade unions could play in ensuring a Just Transition away from fossil fuel use is equitable.

With their diminished power, it is likely that any ‘green’ transitions will favour the corporations and their mates in the financial markets, which means the shift will just reinforce the neoliberal trends.

More on that another day.

Conclusion

Trade unions were once a great industrial and political force in our societies and as JK Galbraith surmised – were responsible for somewhat

‘taming’ capitalism.

Those glory days for workers are gone and the future remains bleak.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.