Otaviano Canuto and Sebastian Carranza

Original post at the Policy Center for the New South

A proposal to dollarize Argentina’s economy reached its Congress in March. As this route occasionally appears as a proposal in Argentina, we summarize here the potential consequences of such a move.

First, we point out broadly the implications of dollarizing an economy. Then, we check relevant Latin American experiences with dollarization. Finally, we address the case of Argentina.

Argentina’s fiscal imbalances will not be eliminated by dollarization. Even though dollarization would prevent the printing of money, it imposes no constraints on government spending and borrowing. The only result is that monetary policy ceases to be available as an option, leaving almost no response capacity in case of external shocks. Moreover, dollarization creates the possibility of being exposed to pro-cyclical monetary policies unrelated to domestic necessities. It also eliminates seigniorage benefits.

Latin American experiences of dollarization have been followed by attempts by Ecuador and El Salvador to find a way out of it. However, once dollarization is implemented, it is extremely hard to backtrack. So far, there is not a single relevant case anywhere of successful de-dollarization.

Argentina’s central bank has insufficient dollar reserves to match the monetary base. The monetary base (or M0) is the total amount of a currency either in general circulation in the hands of the public, or in the form of commercial bank deposits held in the central bank’s reserves. The creation of money (dollar deposits) by domestic banks needs M0 to be dollar denominated.

Proposing dollarization under current conditions would require a selective default of domestic currency liabilities, a brutal devaluation, and/or unilateral conversion of public deposits. None of these are emphasized by those who have made dollarization proposals.

Based on the general implications, the Latin American experiences, and the implementation difficulties, we discuss how these ideas are unfeasible in Argentina now.

Why Discuss Dollarization of Argentina Today?

In 2001, Kenneth P. Jameson published an article titled ‘Dollarization in Latin America: Wave of the Future or Flight to the Past?’ He argued that the region was moving towards dollarization and that changing the legal currency to the U.S. dollar represented the “last gambit” for Argentina’s president at that time, Fernando De la Rua. Kurt Schuler and Steve H. Hanke (2001) published an article titled: “How to dollarize in Argentina now”, in which they proposed four steps towards dollarization in order to “help Argentina return to an economic growth path”.

Even though these proposals never materialized, they were kept on the shelves, waiting for the right moment to reemerge. In March 2022, an Argentine lawmaker—Alejandro Cacace—proposed a bill to dollarize the Argentine economy. One of the candidates for the next presidential election in 2023, Javier Milei, announced he intended to call a referendum to achieve this goal (Burns, 2022). Moreover, local and foreign economists, including Nicolas Cachanosky (American Institute for Economic Research) and Steve Hanke (Cato Institute), have argued that dollarization for Argentina is “the only way out to avoid hyperinflation”.

What is Dollarization?

In general terms, ‘dollarization’ is often used to refer to residents holding a significant share of their assets in foreign currency. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the U.S. dollar is the main currency gravity center.

It is vital to illustrate the difference between de-jure and de-facto dollarization. The first refers to the case in which foreign currency is given legal tender status, which implies that the foreign currency is used legally for the three functions of money (store of value, unit of account, and medium of exchange). On the other hand, de-facto dollarization represents the situation in which the foreign currency is being used alongside the domestic currency, but not with an equivalent legal status. The most common case in Latin American countries is saving in hard currency. De-facto dollarization may take place to different degrees. Countries transitioning towards de-facto dollarization are called ‘bi-monetary economies’[1].

Another distinction is between domestic dollarization, when financial contracts between domestic residents are made in foreign currency, and external dollarization, which covers financial contracts between residents and non-residents.

What Are the Implications of Fully Dollarizing an Economy?

Dollarization is a step beyond choosing between fixed versus floating exchange rate regimes and full convertibility between domestic and foreign currencies.

A first consequence is the loss of seigniorage (the difference between the cost of production of money and its face value)[2], or its corollary: financing other nations’ seigniorage. There are two components to the seigniorage loss implied by dollarization: 1) An immediate ‘stock’ cost. To withdraw domestic currency from circulation, the monetary authority would have to purchase the M0 stock of domestic currency in exchange for U.S. dollars, returning the accumulated seigniorage earnings accumulated over time. 2) The monetary authority gives up future seigniorage earnings from the flow of new printing to satisfy money demand.

A second consequence is that proactive monetary policy ceases to be available, and the dollarized economy becomes tied to another country’s monetary policy decisions.

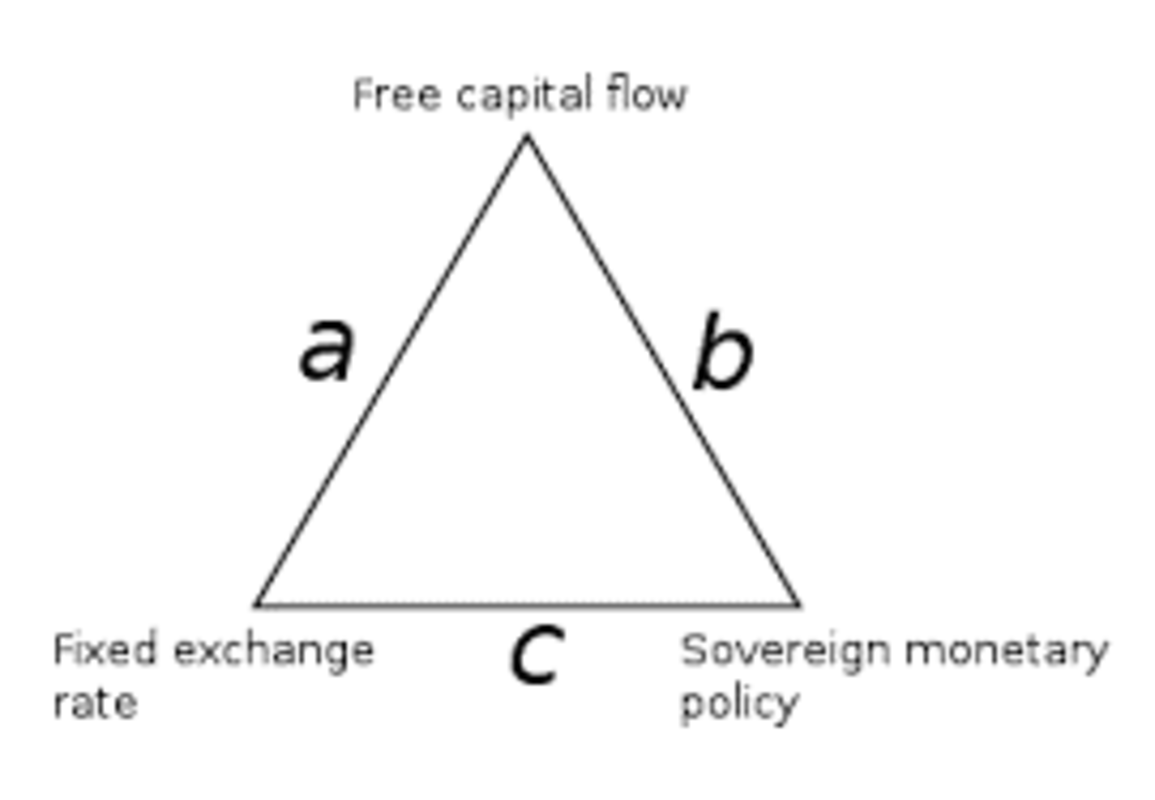

Difficulties in implementing pro-active monetary policies are already present with fixed exchange rates under conditions of free capital mobility, as stipulated by the trilemma of international finance, also known as the ‘impossible trinity’ or the Mundell-Fleming trilemma (Figure 1). There is always a potential conflict between the exchange-rate fixed commitment and sovereign monetary policy when capital flows freely to a country.

Dollarization is a radical move away from any fixed exchange rate regime. Furthermore, as M0 moves beyond the control of domestic monetary authorities, the latter are no longer capable of implementing proactive monetary policies.

Figure 1: Impossible trinity

This is particularly problematic when the domestic economy is not deeply correlated with the economy of the country of the adopted currency. This is the “optimum currency area” argument also developed by Robert Mundell (1961). In other words, the dollarizing country not only loses the possibility of applying counter-cyclical monetary policies, but also might be exposed to inappropriate monetary policies from another nation. However, as stated by Mundell, abdicating from one’s own counter-cyclical policies would not be a major problem if shocks affecting the area as a whole are similar—a condition favorable to monetary integration. Free mobility of labor in the monetarily unified area also facilitates the absorption of shocks.

That is why monetary unification of areas—such as when the euro area was created—comes accompanied by several other reforms. Besides labor and capital mobility, a common fiscal framework needs to be implemented, as along with harmonization of financial regulation. To a great extent, the euro-area crisis after the global financial crisis exposed the incompleteness of the complementary reforms (Canuto, 2021).

A third consequence of dollarization is the restricted scope for lender-of-last-resort operations. Generally, central banks function as the ultimate guarantor of the financial system’s stability in case of a bank run. In the case of a fully dollarized economy, the central bank loses the ability to print money, meaning that in a scenario of a generalized loss of confidence in banks, the central bank would be unable to guarantee the whole payment system or to back bank deposits fully.

Cachanosky (2022) dismissed this as a weak factor against dollarization in Argentina. He remarked that bank runs in the country cannot be countered with domestic-currency money, as dollar exit predominates and running agents will not take local-currency bonds. He also referred to the possibility of self-administered pools of bank deposits complying with that function without the need for a public pool of reserves. He pointed out the operation of emergency liquidity funds in Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama.

In any case, proactive monetary policies are given up. Not by chance, Cachanosky praises dollarization for exactly doing this. It would be a sort of acknowledgment by the country that it should not have discretionary decision power over monetary subjects.

What would be the advantages of dollarization? It would in principle solve almost instantaneously the domestic inflation[3] problem. This does not mean that there will be no inflation, but—given the absence of exchange rate fluctuations, and assuming economic integration— the gravity center would be U.S. inflation, which is usually lower than inflation in Latin American economies[4].

A second positive element of dollarization would be the reduction of the risk premium associated with exchange-rate fluctuations. Therefore, following the interest parity condition, the domestic interest rate would diminish, supposedly increasing investment and potential GDP levels.

A third benefit, only observable in the long run, would be the elimination of currency crises and the macroeconomic instability that they bring.

There is also one relevant factor from the standpoint of long-term policy making: dollarization is nearly irreversible. Once you are in, it is extremely difficult to get out. As we will see in the next section, many people in Ecuador and El Salvador have been trying unsuccessfully to figure out how to leave dollarization for more than a decade.

It should be noted that the attribution of stability as a guaranteed outcome of abdicating the local currency and domestic monetary policymaking reflects a view that reduces all instability to the monetary sphere. Real-side shocks no longer have monetary policy as occasional shock absorbers. The larger a country, and the more dissociated from the mother-currency it is, the more unilateral foreign-currency adoption—not accompanied by euro area-like reforms—will leave the adopter subject to the risk of living with the local transmission of monetary policy options that are not appropriate for local circumstances. Getting rid of past monetary mismanagement does not mean automatically that appropriate monetary settings will replace it.

Some Latin American Experiences

Ecuador

Ecuador is a case of de-facto dollarization. An economic crisis triggered this process at the beginning of the century. By comparing its experience with other countries of the region, including Argentina, we can infer that Ecuador’s macroeconomic disequilibrium could have been resolved without such a drastic regime change. However, a counterfactual analysis in this case would have to be made.

Related to what we pointed out, the Ecuadorian experience shows that dollarization de facto reduced inflation at the expense of increasing the volatility of the economic cycle.

The most important conclusion regarding Ecuador’s experience is that changes in the monetary regime do not solve structural economic problems, such as lack of productivity growth or—in Ecuador’s case—excessive oil dependence. After dollarizing an economy, if the old economic structure remains, it can still have debt crises, as Ecuador recently did. Therefore, it is not a surprise that many political leaders have analyzed ways to de-dollarize Ecuador. Paradoxically, leaving this regime might have more brutal consequences than those which motivated its adoption.

El Salvador

This de-facto dollarization occurred after a unilateral decision of the Salvadorian government during the first year of the new millennium. The expected results were financial integration, lower inflation, and diminishing domestic interest rate volatility. Instead, some of these variables showed modest improvements but at a high cost.

After dollarizing, El Salvador showed a positive effect in terms of commercial integration. Nevertheless, correlation does not imply causation. Levy Yeyati (2012) showed that the whole Caribbean region raised its levels of trade openness during those years. Moreover, he applied a gravity model in which the dummy common currency with the U.S. had a negative and significant effect on the expected trade gains.

In terms of inflation, El Salvador stood below other countries in the region both before and after dollarization.

One of the main costs of dollarization was seen in fragility to external shocks. Comparing El Salvador’s response to the 2008 financial crisis to its regional neighbors, both in activity and financial terms, El Salvador appears to be among those most affected by the crisis.

Finally, in terms of growth and volatility, any simple comparison of the 1990-2000 (before dollarization), and 2000-2010 (after dollarization), periods shows that El Salvador’s growth pattern in terms of both levels and volatility has not differed visibly from those of its neighbors.

Argentina: Dollarization Ahead?

At the beginning of each semester, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon Kuznets used to say to his Harvard students: “There are four kinds of countries in the world: developed countries, undeveloped countries, Japan, and Argentina.”

Argentina has been through one of the greatest economic reversals of the past century. A country with abundant natural resources and outstanding human capital that once had GDP per capita higher than the U.S. has deteriorated continuously to its current level.

Argentina has been dealing with inflation for almost seven decades. After peaking in 1989 (with hyperinflation), the government of Carlos Saul Menem opted for a currency board, inspired by the Hong Kong experience during the 1980s. It was a fixed exchange rate regime with the equivalence of 1 U.S. dollar = 1 Argentine peso. Despite its immediate effectiveness in dealing with inflation, this regime created macroeconomic difficulties that ended with the greatest economic crisis in Argentina’s history. Even though the monetary regime did not cause the crisis, it contributed to hiding the macroeconomic disequilibrium beneath it.

As we have already remarked, it is very complicated to abandon any ultra-rigid exchange rate regime. It creates a dissociation between the technical diagnostics and the population’s beliefs. In 2000, surveys in Argentina showed that a significant majority of the population wanted to keep the 1-to-1 parity, despite having lost any sustainability.

The first argument against dollarization in Argentina is linked to the idea expressed above. Dollarization creates a dissociation between what the economy needs and what voters demand. Dollarization influences politicians towards short-term solutions instead of what technical analysis might suggest.

The second argument is that dollarization would not solve the real problem behind Argentina’s continuous decline: productivity. As Nobel Prize-winner Paul Krugman once said, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it’s almost everything”. Even though someone might argue that the reduction in the domestic interest rate (less risk premium) will help investment, and therefore productivity, this is not sufficient. Argentina’s productivity problem has two roots related to one another: lack of competition because of protectionism, and government inefficiencies transferred to the private sector. Neither of these will be solved by simply dollarizing the economy. Moreover, the problem might worsen for a third reason, as follows:

Argentina’s fiscal deficit will no longer be covered partially by the inflation tax. By losing control of monetary policy, the government will lose one of its primary sources of financing. Even though it is a healthy policy to limit monetary financing through fiscal deficits, the result could go in one of two directions. If the government decides to reduce its spending, Argentina might follow a ‘good equilibrium’ path[5]. But there is a more attractive solution for politicians, which is less costly in political terms: raising taxes. If Argentina takes this second alternative, it will enter a ‘bad equilibrium’ path, and productivity will decline rather than increase.

So far, the main benefit of replacing the domestic currency with a foreign currency would be the use of the latter as a nominal anchor of expectations. Fiscal discipline is a requirement of dollarization processes. But then, why is dollarization needed in the first place? Is not fiscal discipline sufficient to calm expectations and return to the growth path? Is it worth losing monetary policy for this extra lock-in?

Cachanosky (2022) argued that dollarization has helped Ecuador avoid falling into the trap of populist and unsustainable fiscal policies that led Venezuela to its collapse. In fact, as he recognized, a dollarization of Argentina would be part of a recognition that the country is incapable of managing itself fiscally and monetarily.

Shutting down monetary policy would leave Argentina defenseless against external shocks (unless somehow dollarization by itself managed to generate reserves and debt capacity, which is not obvious). A clear example of this situation was the insufficient fiscal response to COVID-19 in dollarized economies. For countries the size of Argentina, adopting a passive stance to foreign shocks may be far from optimal.

Unlike some European experiences, Argentina has neither enough reserves nor credit support from developed economies such as France or Germany to offset the consequences of external shocks. Therefore, is it wise to give up the only tool left? Abdicating from monetary and fiscal policy autonomy may be too exaggerated a move because of previous policy mismanagement.

Argentina has proved Simon Kuznets right again when it comes to imposing discipline to monetary policy. In 2001, when Argentina was suffering a liquidity crisis and the currency board restricted monetary issuance, the treasury and some provinces decided to issue local bonds[6] that, in practice, worked as currency. These ‘bonds’, colloquially called ‘quasi currencies’, were used by governments to pay public-sector wages, and inject liquidity into the system in the middle of the crisis. This experience showed that ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ and that fiscal discipline is not guaranteed under a fixed monetary regime, and much less so in a dollarized economy.

Another argument is the difficulty of reversing such a change once it happens. Take the case of the Argentine experience of leaving behind the currency board. Dollarization is an even more extreme measure, through which the domestic currency would be completely eradicated. Nevertheless, if the theory is not enough to convince the reader, two different cases (Ecuador and El Salvador) are still now, 20 years later, trying to figure out how to abandon their regimes. El Salvador is experimenting with cryptocurrencies, while Ecuador has not found an alternative yet.

A final argument is related to implementation. Sometimes the implementation is ignored, but it is a fundamental issue. The central bank must absorb all its liabilities in domestic currency in exchange for U.S. dollars. But this is not only M0; it includes debt titles (Pases, LELIQ y NOTALIQ, etc.) and deposits. Therefore, the obvious questions are: how? And, at what rate would the absorption be?

In 1990, before the currency board, the Argentine government converted public deposits to ‘Bonex 89’ bonds to be repaid ten years later, which meant a drastic decrease in M2, and facilitated the installation of the currency board a few months later. Are promoters of dollarization considering any of these measures?

The situation now is not very different. Argentina’s central bank has no reserves, the monetary base was 3.661 trillion pesos, and the official exchange rate in March 2022 was 110 pesos per dollar. This means that Argentina would need a $33 billion dollars loan not to devalue[7] (assuming no extra reserves for banking system liquidity). In a very optimistic scenario, Argentina receives a loan of $12 billion (using $5 billion as a reserve for the banking system and $7 billion to dollarize the monetary base), the exchange rate of the dollarization would be at 523 pesos per dollar[8]. A devaluation of 375% will have worse consequences than the problems dollarization is supposed to resolve. Argentine salaries in U.S. dollars would be among the lowest globally, and poverty would rise to unprecedented levels. Not by chance, some analysts say that hyperinflation would have to come before any dollarization plan might be put into action.

Bottom line

Paul Krugman wrote a book titled Arguing with Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future, with the aim of understanding why some ideas keep reappearing even though they have been proved wrong empirically and theoretically.

Dollarization of Argentina is a ‘zombie’ economic idea that reappears at times of uncertainty. It has been proven inefficient as a solution to structural problems. Moreover, it creates new problems as complex as the original ones. Once dollarization is pursued, there is no easy way out. Therefore, governments must think wisely before choosing such a drastic monetary regime change.

Any dollarization proposal has underneath a trade-off between the short term and long term. While it has the benefit of reducing inflation almost instantaneously, it would have significant and permanent consequences in the long run, as we have shown.

The reason these ideas keep reappearing in Argentina is a combination of nostalgia and short-term memories. Some people yearn for those years when the currency board brought high returns in dollars. The idea that the clock can be turned back to revive a past that once momentarily existed is not only an Argentine phenomenon; it is also why nationalism has reemerged, and populist leaders have gained power worldwide. Paradoxically, the proposal for dollarization in Argentina would mean an abdication of national self-determination.

Bibliography:

× Burns, Nick (2022). “Javier Milei’s Unexpected Rise”, Americas Quarterly, April 11.

× Cachanosky, N. (2022): “Dolarización: algunas lecciones Internacionales”, INFOBAE, April 10..

× Calvo, Guillermo A., (1999) “On Dollarization,” mimeo, University of Maryland, April.

× Canuto, Otaviano, (2021): “Climbing a high ladder: development in the global economy”, Policy Center for the New South.

× Ize, A. y A. Powell (2004): “Prudential Responses to De Facto Dollarization”. IMF Working Paper 04/66 (Washington, D.C. Fondo Monetario Internacional). Journal of Policy Reform, vol. 8, n.º 4 (2005), pp. 241-62

× Jameson, K. P. (2003). Dollarization in Latin America: Wave of the Future or Flight to the Past? Journal of Economic Issues, 37(3), 643–663

× Krugman (2020) Arguing with Zombies : Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better America. Norton & Company, Incorporated,

× Levy Yeyati, E., and F. Sturzenegger (2002): “Dollarization: A Primer,” in Dollarization, Levy Yeyati, E. and F. Sturzenegger, eds., MIT Press.

× Levy Yeyati, E. (2012). Balance de la dolarización en El Salvador. Elypsis / UTDT / Brookings.

× Levy Yeyati, (2021). “Financial dollarization and de-dollarization in the new millennium,” Department of Economics Working Papers wp_gob_2021_02, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella.

× Mundell, Robert (1961). A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. The American Economic Review, Vol. 51, No. 4 pp. 657-665

× Schuler & Hanke (2001). “How to dollarize in Argentina now”. Cato Institute Web paper

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.

Sebastian Carranza is a student at the MA in International Economic Policy at GWU. He holds a BA in Economics at the University of Buenos Aires, and MA in International Studies at University Torcuato Di Tella.

[1] Term also used to describe economies with money demand for two currencies.

[2] Economists understand seigniorage as a form of inflation tax, returning resources to the currency issuer. Issuing new currency, rather than collecting taxes paid with existing money, is considered a tax on holders of existing currency.

[3] Inflation is a regressive phenomenon meaning it affects relatively more to those who have the less. This means that ceteris paribus, dollarization might be seen as a progressive policy.

[4] With a few exceptions such as Peru, Chile, Colombia, etc.

[5] Leaving aside all the difficulties to reduce spending, Argentina’s government expenditure is mainly with pensions and subsidies to energy and transport. Unpopular structural reforms remain necessary despite risks of political instability.

[6] Treasury bonds: “Lecops”; Buenos Aires bonds: “Patacones”; Cordoba bonds: “Lecor”, etc

[7] It is helpful to remember Argentina faces very high premium risks and a program with the IMF that simply rolls-over previous debt with the institution.

[8] and this is just to absorb M1. If we consider all the liabilities the devaluation would need to be more than double.