Charter Communications Inc. and Cox Communications Inc. have announced a plan to merge in a $34.5 billion deal. The transaction would create the nation’s largest cable operator, surpassing Comcast, with approximately 38 million subscribers across 46 states.

Predictably, the proposal triggered concerns about cable-industry consolidation. Yet the reflexive anxiety about “big cable getting bigger” misses the economic realities of today’s communications marketplace. A regulatory review of this merger deserves a clear-eyed analysis based on sound economic principles, rather than outdated regulatory frameworks or political agendas.

Today’s Multi-Platform Reality

To understand this merger’s competitive significance, it should be noted that the term “cable operator” has become increasingly meaningless. Indeed, the communications landscape of 2025 bears little resemblance to the era when most regulatory frameworks governing the sector were established.

The “cable company” of yesteryear—a regulated monopoly providing video programming to the home or business—is long gone. Today, these businesses compete among many options to provide video programming, broadband internet, and mobile services.

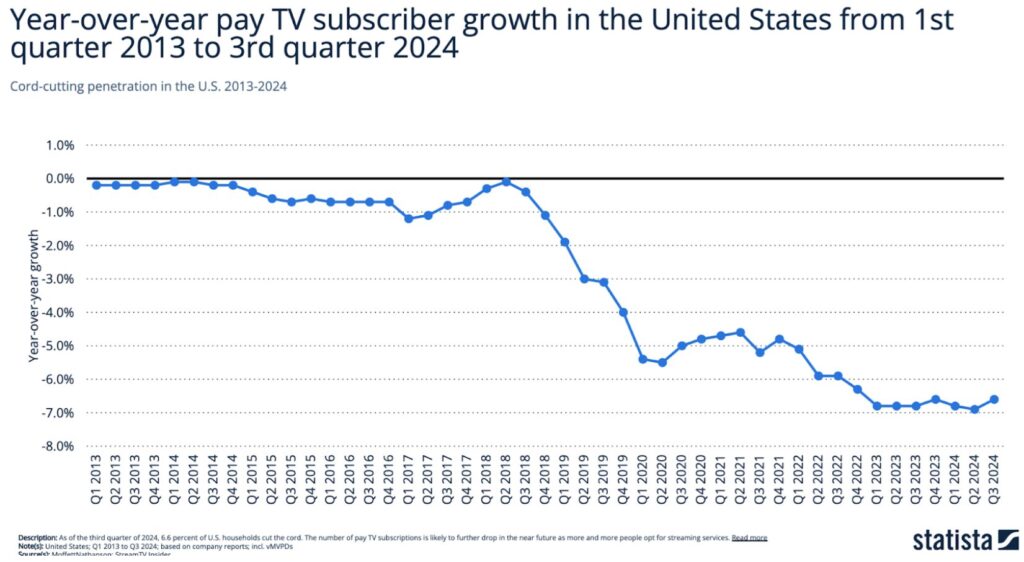

Cord-cutting statistics tell the story: an estimated 107 million Americans have already abandoned traditional pay TV, leaving us with more non-pay TV households (77.2 million) than those still subscribing to traditional services (56.8 million). Charter’s recent quarterly results revealed a 7.3% decline in video customers year-over-year, and an 8.4% drop in video revenue. Cord-cutting isn’t a temporary trend but a fundamental market transformation.

Meanwhile, as the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE) reported, broadband competition has intensified dramatically.

- Fiber deployment continues to expand, with the U.S. fiber-optic market projected to grow 8% annually through 2032.

- 5G fixed-wireless access has emerged from a novel innovation to a disruptive competitor. According to ICLE, 5G technology was first rolled out in 2018; today, 77% of operator locations have 5G. Grand Review Research projects 5G’s North American market is expected to grow from $12.6 billion in 2024 to $91.8 billion by 2030, an annual growth rate of nearly 40%.

- Satellite broadband, once a last resort for rural consumers, has become increasingly viable through low-earth-orbit networks like Starlink, which doubled its subscribers in 2024.

Against this backdrop, the proposed Charter/Cox merger represents a strategic adaptation to these competitive pressures, rather than an attempt to monopolize existing markets. The combined entity will need to achieve significant efficiencies to remain viable in this rapidly evolving landscape.

Merger Specifics: Expansion vs Consolidation

Unlike previous failed consolidation attempts in the cable industry—most notably, Comcast’s 2015 bid for Time Warner Cable—the Charter/Cox proposal combines largely non-overlapping geographic footprints. This distinction is crucial for antitrust analysis. Rather than eliminating head-to-head competition in local markets, this transaction resembles a geographic expansion that allows the combined company to achieve greater scale across different regions.

This scale matters for reasons beyond market share. The communications industry requires massive capital investments to deploy advanced technologies. The combined Charter/Cox projects $500 million in annualized cost synergies. If realized, these savings could be invested in network upgrades (e.g., expanding gigabit and multi-gigabit capabilities, and accelerating deployment of the DOCSIS 4.0 internet-communications standard); product-offering innovations (such as converged mobile and broadband bundles, where a larger entity might secure better mobile-virtual-network-operator (MVNO) terms); and improved customer service.

Regulatory Hurdles: DOJ and FCC Review

The merger faces regulatory reviews from both the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), each applying different standards and potentially pursuing different agendas.

The DOJ will evaluate the transaction primarily under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which prohibits mergers that may substantially lessen competition. Under sound antitrust principles, this analysis should focus on demonstrable, substantial competitive harms in properly defined relevant markets. Given the minimal geographic overlap between Charter and Cox, and the vibrant multi-modal competition both face, the merger appears unlikely to trigger legitimate competitive concerns under a consumer welfare standard.

Alas, the prevailing environment for antitrust enforcement has increasingly diverged from decades of economically sound, consumer-focused policy. The 2023 Merger Guidelines adopted by the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reflected a “neo-Brandeisian” approach that is often dismissive of efficiencies, and hostile to consolidation regardless of the competitive effects. This ideological shift risks blocking transactions that benefit consumers through innovation and investment.

The FCC’s review presents additional complications due to its nebulous “public interest” standard—a framework that has historically allowed the commission to extract concessions unrelated to competitive concerns. In comments to the FCC’s “Delete, Delete, Delete” initiative, ICLE concluded:

The current expansive interpretation has allowed the Commission to address matters only tangentially related to the transaction at-hand, effectively turning merger reviews into de-facto rulemaking proceedings. This approach creates substantial regulatory uncertainty and violates the principle that regulatory interventions should be narrowly tailored to address specific, demonstrable harms.

Reports that FCC Chairman Brendan Carr might leverage the merger-review process to target companies’ diversity and inclusion policies exemplify the troubling politicization of regulatory processes. Such mission creep undermines rule-of-law principles and creates regulatory uncertainty that harms investment.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo offers a potential check on such regulatory overreach by constraining agencies’ ability to interpret their authority expansively. This precedent could become important if the FCC attempts to impose conditions unmoored from clear statutory authorization.

Market Definition: The Critical Question

Perhaps the most consequential question that regulators will need to answer is how to define the relevant market. Focusing narrowly on “cable subscribers” or wired-broadband shares in isolation would fundamentally misrepresent the prevailing competitive dynamics. In addition to cord-cutting, today’s consumers increasingly “de-bundle,” mixing and matching services from various providers, such as combining fiber broadband with multiple streaming subscriptions and a separate mobile plan.

This behavior makes traditional market-share calculations less indicative of actual market power. Concentration metrics like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) become misleading when applied to artificial market segments that ignore the substitutes consumers actually use. Regulators must recognize that market boundaries have blurred substantially, with telecommunications companies, wireless carriers, and technology firms competing in converged-service markets.

Asymmetric Regulation: An Uneven Playing Field

The regulatory scrutiny facing Charter and Cox starkly contrasts the treatment of equally consequential developments in adjacent markets. While cable operators face intensive reviews for horizontal mergers, technology giants can expand their communications and content offerings with minimal oversight. As I noted in an earlier post, this regulatory asymmetry disadvantages traditional providers without clear consumer benefits.

Companies like Amazon, Google, and Netflix now dominate video viewing time, yet face little of the regulatory burden imposed on cable operators. Similarly, wireless carriers aggressively expanding into home broadband face fewer legacy regulations than their cable competitors. A coherent regulatory framework would address these disparities by reducing burdens on traditional providers.

Consumer Welfare: The Proper Standard

Despite current trends in antitrust enforcement, the consumer welfare standard remains the most economically sound and workable approach to merger analysis. This framework asks whether a transaction will harm consumers through higher prices, reduced output, diminished quality, or hampered innovation—harms that must be weighed against merger-specific efficiencies.

The proposed Charter/Cox combination will likely face significant regulatory pressure to offer concessions around pricing, network expansion, service quality, and possibly DEI (\diversity, equity, and inclusion) policies. While some targeted conditions that address demonstrable competitive concerns may be appropriate, regulators should resist demands for commitments unrelated to the transaction itself.

Market forces—particularly from emerging competition—will likely discipline the merged entity more effectively than regulatory conditions. Indeed, onerous conditions may hobble the merged company and, in turn, hamper competition. That’s because, with consumers cutting the cord, fiber providers expanding their footprints, wireless carriers pushing fixed-wireless access, and satellite broadband improving rapidly, even a larger Charter will face substantial competitive pressure. Complying with conditions unrelated to the merger’s competitive effects would put the new company at a relative disadvantage.

A Path Forward: Economic Realism in Regulatory Review

Several principles should guide policymakers as the Charter/Cox merger moves through the regulatory process. Most importantly, reviews should focus on demonstrable, transaction-specific competitive harms, rather than abstract concerns about size or concentration. Given the limited geographic overlap and intense multi-modal competition, the standard for proving harm should be appropriately rigorous.

Regulatory frameworks should evolve to reflect market realities, rather than perpetuate artificial distinctions between service categories or providers. A technology-neutral approach would better serve both competition and consumers.

In addition, efficiency claims deserve serious consideration, particularly in capital-intensive network industries with substantial scale economies. The potential for accelerated network upgrades and enhanced service offerings represents genuine consumer benefits that should not be dismissed.

As noted above, any conditions imposed should be narrowly tailored to address specific competitive concerns, rather than advance unrelated policy objectives. Using merger reviews as leverage for broader regulatory agendas undermines legal certainty and discourages pro-competitive transactions.

Regulators should ground their analysis in sound economic principles that recognize today’s competitive reality: a dynamic, multi-platform ecosystem where traditional boundaries separating technologies, services, and providers continue to erode. This approach would better advance the interests of consumers, while fostering the investment and innovation needed to strengthen America’s communications infrastructure.