There are ten nations knocking on the European Union’s door.

Looking ahead, they can look back to 2004.

EU Expansion

The benefits of EU expansion look best when we direct our lens at the new nations that joined two decades ago. With Poland’s ascent to #6 in a list of the EU’s largest economies, we have a prototype for how the East grew.

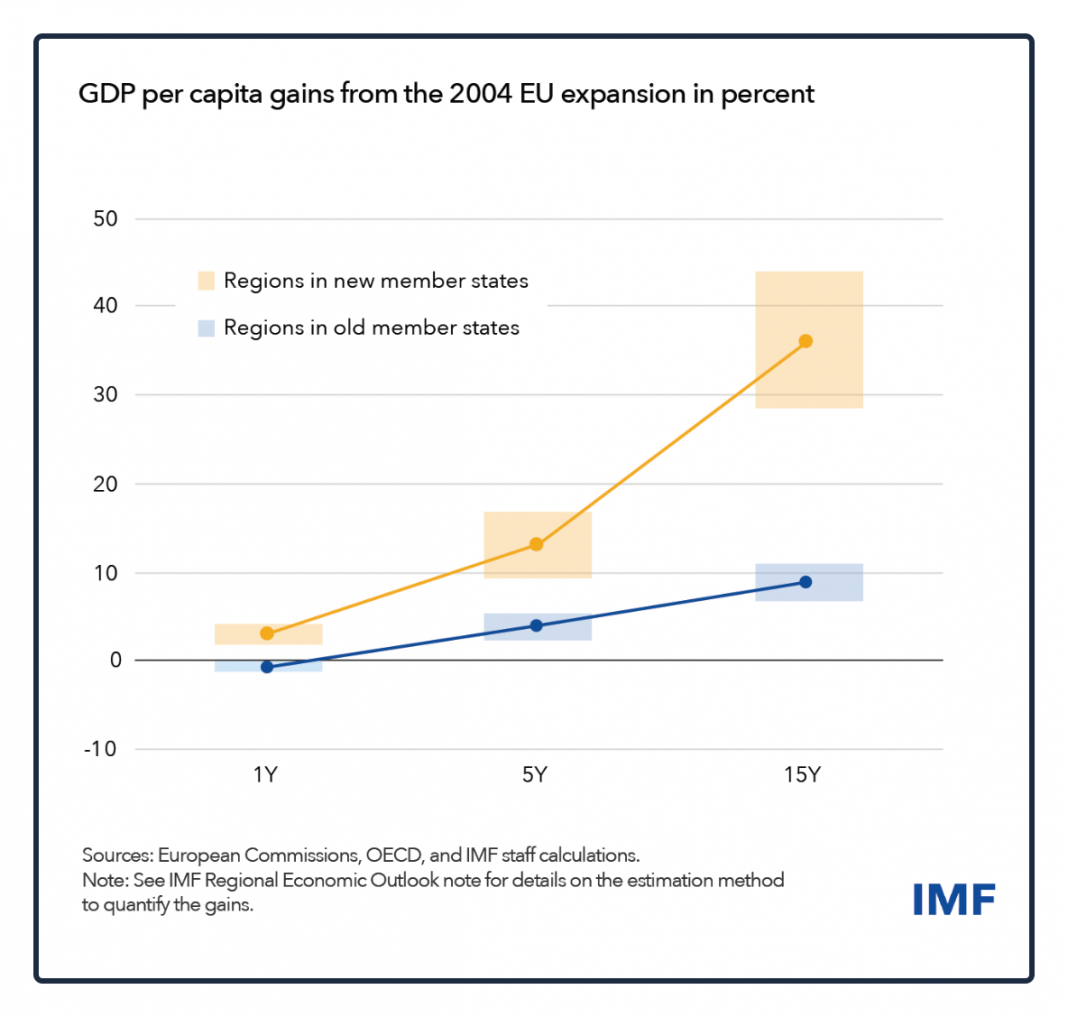

Measured by GDP per capita, new member states’ economies flourished:

During 2004, the ten countries that joined the Eu were Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovenia, Cyprus, Estonia, and Slovakia. Now the IMF tells us that, after 15 years, the new member states’ GDP per person income is 30% higher than it would have been without accession. Further corroborating the impact, researchers estimate that, by 2019, existing EU members’ income per person averaged 10% more than it would have been.

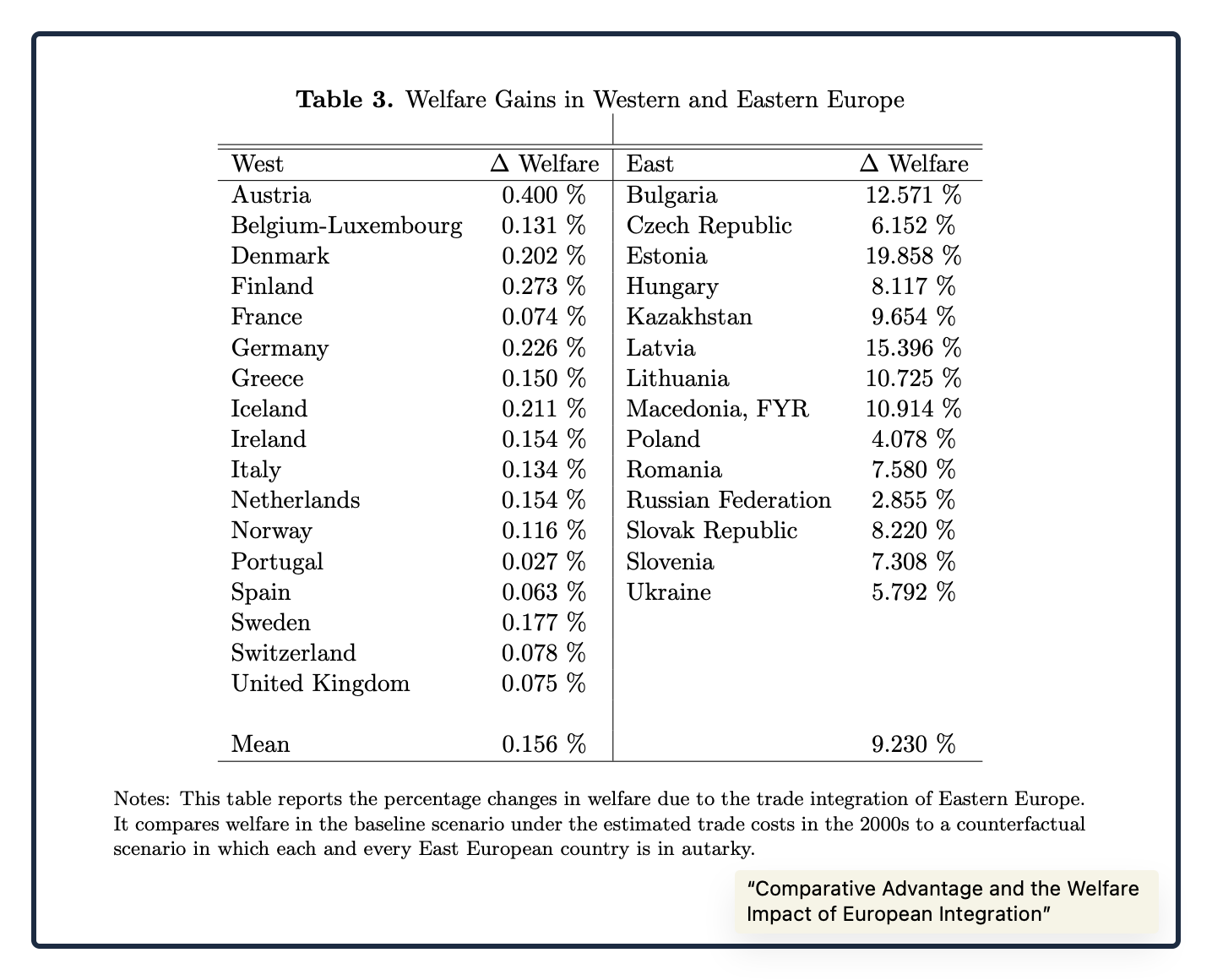

In a 2012 study, University of Michigan scholars concluded that Eastern European nation benefited far more than the West. The reason, they explained, was what the East brought to the table. Because their economies were sufficiently different from Western Europe, they enjoyed more demand. That 2012 paper concluded that East Europe had a 24% share of the West’s imports.

It also compared the West’s and East’s welfare gains:

Our Bottom Line: The Power of Comparative Advantage

It all takes us back to Devid Ricardo’s comparative advantage.

In the United States, during the first half of the 19th century, the completion of a canal network and then a railroad transportation infrastructure enabled a national market to form. As a result, each part of the nation could specialize in what it did best. The Northeast could concentrate on manufacturing, the West could grow farm goods and raise livestock, the South could focus on cotton. What you did not provide locally, you could get from a distant place. Rocky New England farms no longer needed to grow tobacco. People in the South could stop making their own shoes.

Hearing about a national market, 19th century economist David Ricardo would ask us to remember comparative advantage. He would say that each part of the U.S. should produce and trade whatever requires the lower opportunity cost. By sacrificing less than other areas that need more resources to produce the same items, each region becomes more productive.

In the European Union, while the East especially benefited from comparative advantage, the synergy fueled everyone’s growth. Indeed, it was the larger single market that accelerated business firms’ expansion and efficiency.

Considering the 10 nations that now want membership, the EU can recall the impact of the 2004 expansion.

My sources and more: Thanks to this IMF Blog for inspiring today’s post. From there, this NBER paper reaffirmed the value of comparative advantage. But most crucially, to consider EU “enlargement,” this paper presents the ideas we should ponder.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.